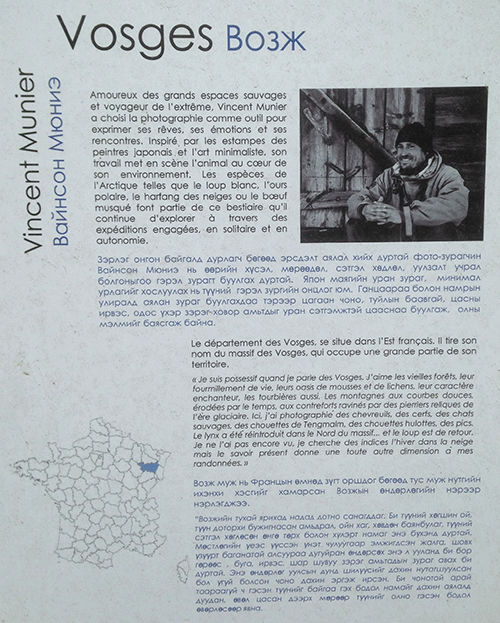

In about February or March 2018, a set of very attractive wildlife photos appeared outside the French Embassy in Mongolia. The photos were by prize-winning French wildlife photographer Vincent Munier and showed scenes of winter wildlife in France.

While the photos themselves were first rate, the translation of the captions raised interesting questions about the translation of bird names.

Of the eight posters, there were three featuring birds: the Boreal Owl, the Eurasian Wren, and the Eurasian Blue Tit.

The French captions all gave the accepted French common names (ornithological names) of the three birds.

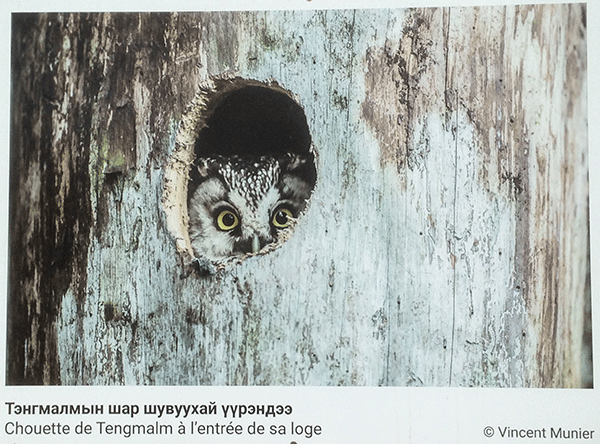

First, the Boreal Owl (Aegolius funereus), a small nocturnal owl that typically lives in tree hollows. Munier has captured a delightful view of this secretive bird in its nest.

The Boreal Owl is known in ornithological French as Chouette de Tengmalm or Nyctale de Tengmalm. In the poster the first alternative is used. 'Tengmalm' is from the 18th century Swedish physician and naturalist, Peter Gustaf Tengmalm, who was originally thought to have been the first to describe the species.

The most general French words for 'owl', as found in dictionaries, are 'hibou' and 'chouette', the former being used for owls with 'ears', the latter for those without. But ornithological naming in French does not restrict itself to these two terms. The ten species of strigid owl found in France are variously known as 'hibou', 'chouette', 'grand-duc', 'petit-duc', 'harfang', 'chevêche', and 'chevêchette'. The Western Barn Owl, which belongs to the Tytonidae, is called an 'effraie'. 'Chouette' is used for the genera Strix, Surnia, and Aegolius.

In Mongolian, the equivalent ornithological name for Aegolius funereus is Савагт ариан savagt ariaŋ, where саваг savag refers to the shaggy hair on a yak's belly, and ариан ariaŋ is an alternative but not commonly used name for the owls that ornithological authorities have restricted to the genus Aegolius. An older ornithological name for Aegolius funereus is Савагт ууль savagt uul', using a somewhat more familiar word for the owls, ууль uul'.

It is clear that the translator has either not been able (or not bothered) to find out the Mongolian ornithological name for this species, or has chosen to ignore it. Instead, he or she has created a new Mongolian name by translating the French ornithological name directly into Mongolian.

Interestingly, however, the translation is not quite a word-for-word rendering. The translator appears to have devoted some thought to creating an 'appropriate' Mongolian name. The Mongolian name in the poster is Тэнгмалмын шар шувуухай (Tengmalmiŋ shar shuvuukhai), literally 'Tengmalm's yellow birdlet'. Тэнгмалмын tengmalmiŋ is transparently 'Tengmalm's'. Шар шувуухай shar shuvuukhai is based on the most commonly used name for the owls in everyday Mongolian, шар шувуу shar shuvuu or 'yellow bird'. What is interesting is the way the translator has swapped шувуухай shuvuukhai 'birdlet' for шувуу shuvuu 'bird' in the name. It shows that the translator is aware that the Boreal Owl is a very small owl. Шар шувуухай shar shuvuukhai 'yellow birdlet' can be understood as meaning 'owlet'.

How the translator has arrived at this curious twist in the name is unclear. Online dictionaries distinguish French 'chouette' from 'hibou' by noting that the former does not have 'ears'. However, there are occasional references to size, for instance French Wikipedia, which notes the bird's small size.

Whatever the process by which the name was arrived at, the translator's rendition is based on translating the French ornithological name 'Chouette de Tengmalm' word by word, rather than finding the equivalent in ornithological Mongolian.

Another bird photographed by Munier is the Eurasian Wren (Troglodytes troglodytes):

This bird was once known in English simply as the Wren as it was the only species in the family found in the Old World. But given that there are 87 species of wren in the New World, the Old World wren has since been renamed the Eurasian Wren.

The French ornithological name for Troglodytes troglodytes is Troglodyte mignon, the 'darling troglodyte'.

The Eurasian Wren is found in Mongolia, where it is traditionally known as Уран бялзуухай uraŋ byalzuukhai, which means something like 'deft/industrious finch-like bird', a reference to its busy industriousness and its well-kept nest. This name was long used by ornithologists, but under the recent 'binomial' approach, which requires ornithological names to reflect the classification into species and genus, it has been changed to Халгайч урагчин khalgaich uragchiŋ. Урагчин uragchiŋ, the genus name, is an old name for the wren that has been revived. The descriptor халгайч khalgaich relates to nettles (халгай khalgai). This mysterious descriptor can probably best be explained by the Russian name for the wren, Крапивник krapivnik, which is related to крапива krapiva meaning 'nettle'. Mongolian ornithologists have simply modelled халгайч khalgaich on the Russian name.

The translator of the caption has ignored both the traditional and ornithological names of the wren to render Troglodyte mignon simply as бялзуухай byalzuukhai 'kind of small finch-like bird'. Бялзуухай byalzuukhai is anyone's idea of a small brown bird and does not refer to any particular species or genus.

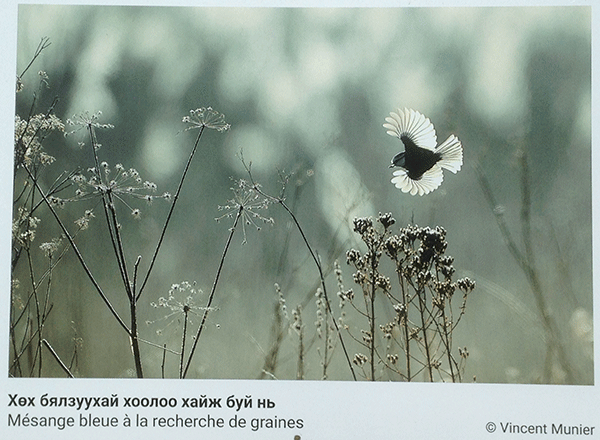

A third photo shows a species that is not found in Mongolia, the Eurasian Blue Tit (Cyanistes caeruleus):

The French ornithological name for the Eurasian Blue Tit is Mésange bleue, meaning 'blue tit'. All members of the tit family (the Paridae) are known in French as 'mésange'.

While the Eurasian Blue Tit is not found in Mongolia, seven other members of the tit family are. They are all known ornithologically in Mongolian as хөх бух khökh bukh, literally 'dark-blue bull'. This is a term that appears in normal dictionaries and is clearly not an exotic or esoteric name.

But rather than use any kind of existing Mongolian name, our translator comes up with the makeshift term хөх бялзуухай khökh byalzuukhai 'darkblue finch-like bird'. Again, the name means little more than 'small blue bird'.

These translations raise several questions.

The first is why such careless and cavalier translations made it into print for posting in a public place. Faced with what are clearly names for particular types of bird, the person tasked with translation has adopted the attitude that, well, anything will do, as long as it makes some kind of sense. Even a bit of casual research would have revealed that 'mésange' is equivalent to хөх бух khökh bukh in Mongolian, and that 'troglodyte' is equivalent to уран бялзуухай uraŋ byalzuukhai. The translator has clearly decided that the vague general term бялзүүхай byalzuukhai, referring to all kinds of finch-like birds, is good enough. For the Tengmalm's owl, the translator has adopted the equally cavalier attitude of translating 'Tengmalm' just because it's there. A little more research would have revealed that 'chouette de Tengmalm' is the name of a specific kind of owl. Either 'Tengmalm' could have been omitted, or an appropriate Mongolian name could have been located.

The second question is, does it matter? After all, the photos are beautiful, the posters are tastefully done, and the appropriate fuzzy feel-good image of French culture will be conveyed to the passer-by. Who cares if the names are fuzzy, too?

This ignores the fact that Vincent Munier is a professional wildlife photographer. There is an introduction to him and the Vosges in front of the posters, presumably to highlight both the beauty of the Vosges region and the degree of excellence that France is capable of. Vincent Munier does not merely take pretty pictures of birdies and animals. Like all photographers of nature, he is aware of what he is photographing. He belongs to a long tradition whereby painting, drawing, and photographing plants and animals is part of the study of natural history, the scientific study of the natural world. The captions on the French posters all make a point of using the correct ornithological names for the three birds. By fobbing Munier's work off on the Mongolian public as nice photos of pretty birds, the translator succeeds in dumbing down Munier's work and revealing his or her own low estimation of the intelligence and intellect of Mongolians. (Incidentally, 'Vosges' is pronounced /voːʒ/ in French, but the Vosges are known as the Vogesen /vo'gezən/ in German and Вогезы vogezy /vogjɛzɨ/ in Russian. For some reason, Mongolian chooses to render the name as Возж vozj /voztʃ/, which accords with no one's pronunciation at all.)

The third question is a more fundamental one. It concerns the Mongolian ornithological names themselves. Theoretically speaking, the captions should have used Савагт ариан savagt ariaŋ, Халгайч урагчин khalgaich uragchiŋ, and хөх бух khökh bukh. But the first two names are clearly right outside the range of intelligibility of the normal resident of Ulaanbaatar. Whereas a reasonably educated person might be expected to understand older ornithological names like Савагт ууль savagt uul' or Уран бялзуухай uraŋ byalzuukhai, it is difficult to see how anyone without a specialised knowledge of ornithology could possibly relate to Савагт ариан savagt ariaŋ or Халгайч урагчин khalgaich uragchiŋ. These names would appear ridiculously technical to most people viewing Munier's beautifully presented photos. By adopting 'binomial names', with the resulting huge distance between ornithological and popular names for birds, ornithologists and scientific experts have effectively insulated their field from contact with the educated public. It is clear that such artificial names will continue to result in the loss of golden opportunities to educate the general public about birds, as in this case of these posters in front of the French embassy.